“Oon mera naam hai, oon oon oon; meri kahani zara sun sun sun.” (My identify in Oon, oon oon oon; take heed to my story.)

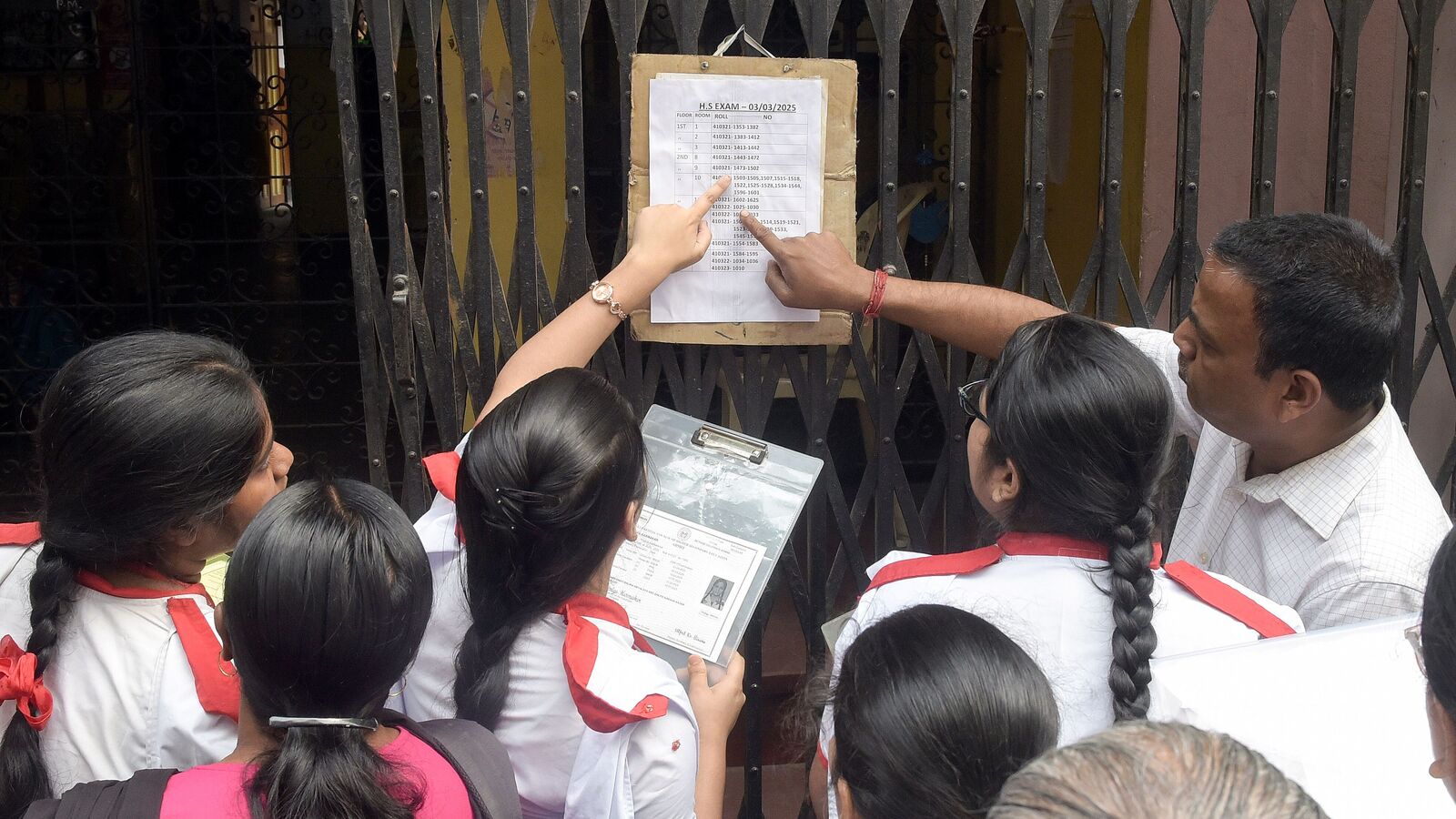

A tuft of uncooked, tangled black Deccani wool with tiny arms and a gap for a mouth bounces throughout the display screen, narrating the story of neglect that desi oon has suffered for generations. The six-minute stop-motion animation movie, Desi Oon, tells a riveting story of how indigenous wool stands forgotten. Its compelling storytelling — depicting the intersection of ecology, dwindling conventional craft, and the risk industrialisation poses to pastoral communities — scooped up the Jury Award for Best Commissioned Film on the prestigious Annecy International Animation Festival final month in France.

The movie was developed over a 12 months by Mumbai-based Studio Eeksaurus, in collaboration with the Centre for Pastoralism, for the Living Lightly – Journeys with Pastoralists exhibition in Bengaluru earlier this 12 months. Filmmaker Suresh Eriyat, founder and inventive director of the studio, who had visited a desi oon exhibition in 2022, says all of it started with listening. “We didn’t go in with a storyboard. We went in with curiosity. The richness of what we encountered — the sheep, the wool, the landscape, and the people who live in that reality — left a deep impact. What excited us most was that this wasn’t just a textile story. It was a story of resilience, of ecosystems, of lives intertwined with the land.”

Filmmaker Suresh Eriyat, founding father of Studio Eeksaurus

| Photo Credit:

Special association

A woolly story

Nearly 30 individuals labored on the movie. Lyricist and singer Swanand Kirkire translated the essence and rhythm of the shepherds’ songs and folks traditions into his lyrics and uncooked singing. The catchy folks tune was composed by Rajat Dholakia, with out utilizing any digital or digital sources, rigorously preserving its natural high quality. And the soundscape was created by Academy Award winner Resul Pookutty.

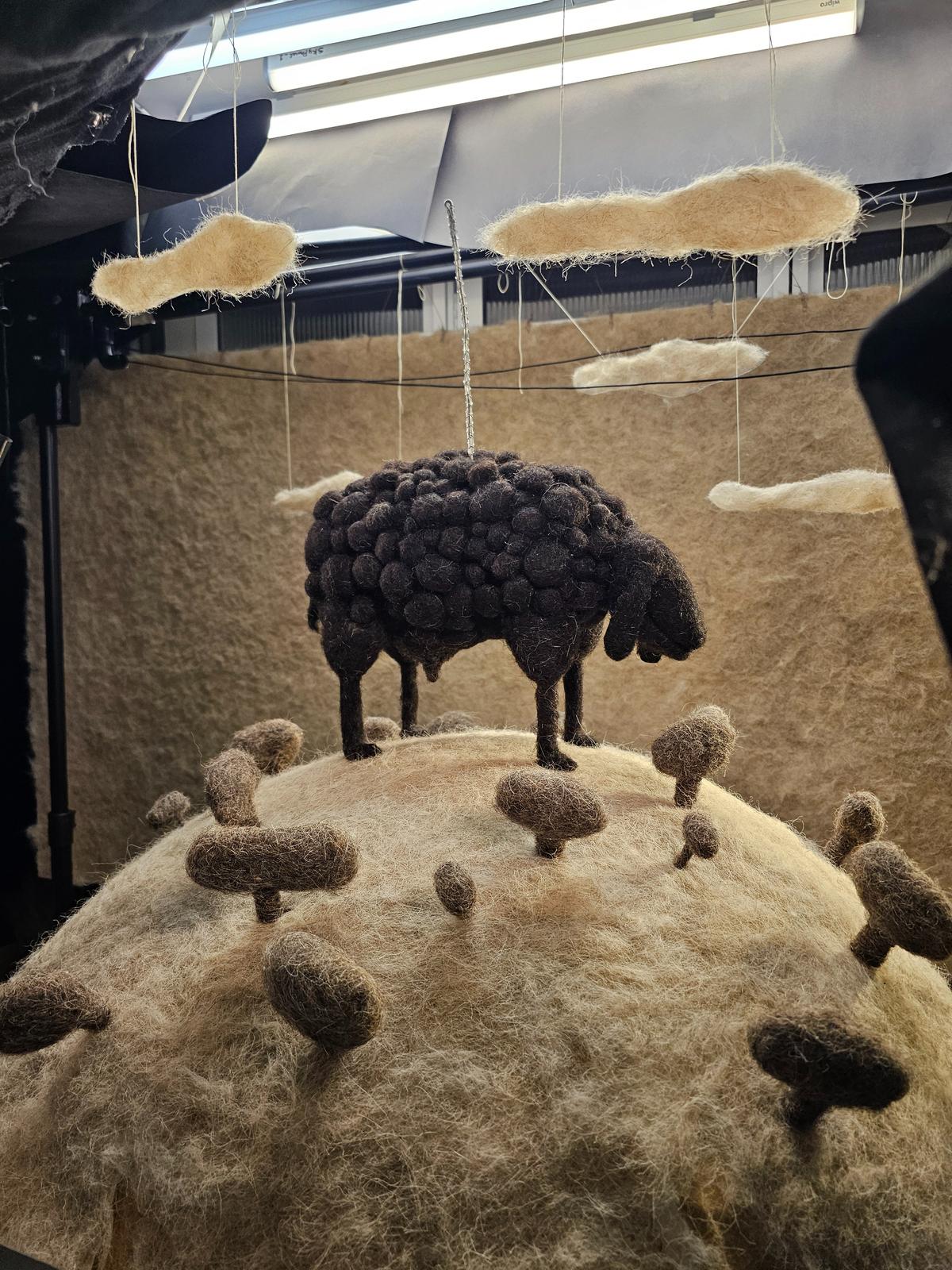

But the star of the present was the desi oon. “We wanted the wool to tell its own story. Wool isn’t sleek. It doesn’t behave. It frays, resists, coils. That unpredictability, usually considered a limitation, was something we leaned into,” says Eriyat, utilizing actual wool from Deccani sheep sourced in Belagavi, Karnataka. “We let the material misbehave. It gave the film a certain life — something beyond what we were breathing into it.”

Making fashions for Desi Oon

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Studio Eeksaurus

They made fashions and used specialised stop-motion methods, a technique which Eriyat describes as “slow, tactile, handcrafted. Just like the lives and materials we were depicting”. But it got here with technical challenges, as animating the wool was painstaking. “Stop-motion gave us the language to do that with poetry, metaphor, and a kind of warmth that invites empathy, not just observation,” he says.

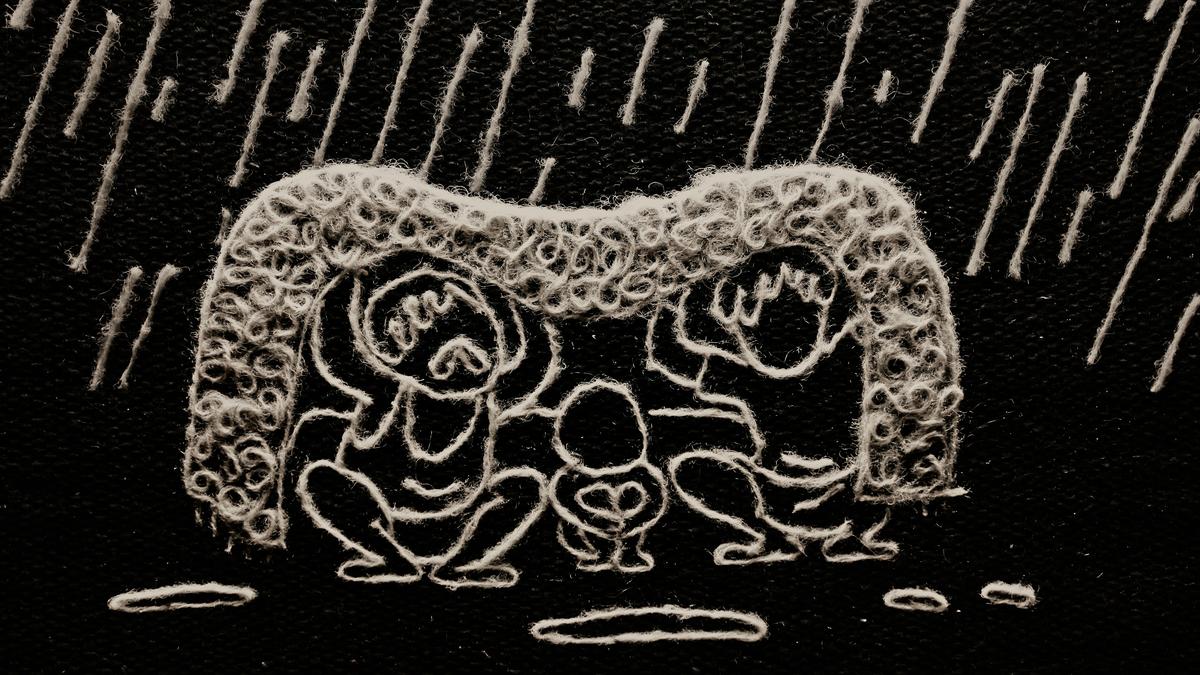

They additionally used specialised stop-motion methods

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Studio Eeksaurus

Embracing slowness turned a part of the storytelling itself. “It echoed the tempo of pastoral life, the rhythm of herding, spinning, weaving, and of course their resilience,” he reminisces of the 12 months they spent engaged on the movie. “In an era of fast content and CGI perfection, this slowness felt almost radical.”

The spirit of Balu mama

Central to the story of Deccani wool is the story of Balu mama, a revered shepherd among the many pastoralists of the area. Known for his quiet management, he devoted his life to nurturing and defending Deccani sheep. The Centre for Pastoralism and the Living Lightly crew linked the studio to the shepherding communities, to stroll with actual pastoralists, observing their rhythm and routines, and study their knowledge handed on orally by means of generations.

Balu mama from Desi Oon

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Studio Eeksaurus

“Watching his followers guide hundreds of sheep across dry, rocky terrain, never raising their voice, just being present, was profoundly moving. The land listens to the flock, and the reverence both the flock and the shepherd held for Balu mama was near worship,” says Eriyat.

His strategy to this collaboration hinged on respect for the craft. “We didn’t want to simplify or romanticise their lives. These communities are complex and proud. So, we took our cues from their stories, songs, silences, and humour,” he says. The metaphors utilized in storytelling had been rooted within the land. “A sheep wasn’t ‘cute’ or ‘comic’. It was central to their economy, their kinship system, and their survival. Even the songs and lyrics were crafted with input from folk musicians who live this life.”

“ When brands co-opt without context, they flatten histories. We need to document not just products, but processes. Not just objects, but origins. And we need to tell them with the same beauty and innovation that global audiences are used to, but with our lens, our voice, our terms.”Suresh Eriyatwho believes the time is ripe for India to share her tales earlier than they’re appropriated by the world

A nonetheless from Desi Oon

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Studio Eeksaurus

Storytelling with craft

The Annecy award was deeply validating for the studio. “Not because of the recognition alone, but because a quiet, rooted story from India resonated on the world stage. It showed us that truth travels,” says Eriyat.

Post the success of the movie, can animation develop into a potent medium for storytelling for craft-led and even luxurious manufacturers? Eriyat believes it might probably, particularly stop-motion, drawing in audiences gently, with out the defensiveness that typically accompanies advocacy. “It makes room for wonder, and wonder leads to curiosity. That’s where change begins. Desi oon has already sparked conversations across sectors, from sustainable fashion and tourism to policy. There have been early inquiries from both luxury brands and government bodies wanting to understand how storytelling like this can be embedded into their communication,” he shares.

A nonetheless from Desi Oon

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Studio Eeksaurus

Eriyat believes animation can develop into a instrument for cultural preservation, craft revival, and even rural financial improvement. “We’ve only scratched the surface. We hope the film becomes a trigger. For young people to ask where their clothes come from. For designers to rethink the supply chain. For policymakers to look again at pastoralism not as ‘backward’, but as ecologically vital.”

The actual success, nevertheless, can be when these communities get sustained consideration and assist. “When their voices are not just preserved, but amplified on their terms.”

The author is a sustainability marketing consultant and founding father of Beejliving, a way of life platform devoted to gradual residing.