Now Reading: How one Indian district is keeping graduates closer to home

-

01

How one Indian district is keeping graduates closer to home

How one Indian district is keeping graduates closer to home

Outside, the late monsoon warmth clung to the air; inside, a brass gong punctuated every speaker’s flip on the microphone.

One official started with pleasure. Hubballi-Dharwad, he stated, had all the time been greater than only a twin metropolis: an academic capital, a cultural centre, a buying and selling hub. “If this experiment succeeds wherever, it ought to be right here,” he instructed the room.

But nearly instantly, the dialog turned to tougher truths. “Every 12 months almost 70,000 college students cross out of Karnataka’s ITIs,” said Ragapriya R., the commissioner of industrial training. “But how many actually fit what industry needs? How many stay in jobs instead of drifting into gig work?”

From the again benches, placement officers rose to add their frustrations. “Our college students need jobs solely inside 15 or 20 km of home, even when Honda or Toyota supply them extra,” said Shivaprakash V. Chitragar, principal of ITI Vidyanagar, Hubballi-Dharwad, recalling how his trainees refused to migrate outside Hubballi-Dharwad. Another spoke of the mismatch between industry expectations—“10 hours, 12 hours of duty”—and what trainees had been prepared, or generally in a position, to tackle.

One speaker reached for a metaphor. Divya Prabhu G.R.J., the district commissioner of Dharwad, in contrast the method of matching employer and worker to a matrimonial web site. “Earlier, matches had been made by phrase of mouth. Today you browse filters—slim, tall, truthful. But does that assure compatibility? No. It takes deeper understanding.” So too with jobs, she argued—mere postings and résumés weren’t sufficient.

Then got here the bluntest instance of all. “There is an ITI on one facet of the highway and an MSME on the opposite—and so they have by no means met,” said another speaker, shaking his head. “The students inside don’t know the jobs exist; the employer across the road never walks in. Both are invisible to each other.”

View Full Image

For a long time, ITIs have been the spine of India’s skilling system: authorities and personal institutes the place college students, largely from low-income households, prepare in trades like welding, carpentry, and electrical becoming. In idea, they’re the bridge to regular work. In apply, placements stay poor—typically beneath 30%—and employers have lengthy criticised the hole between classroom coaching and shop-floor wants.

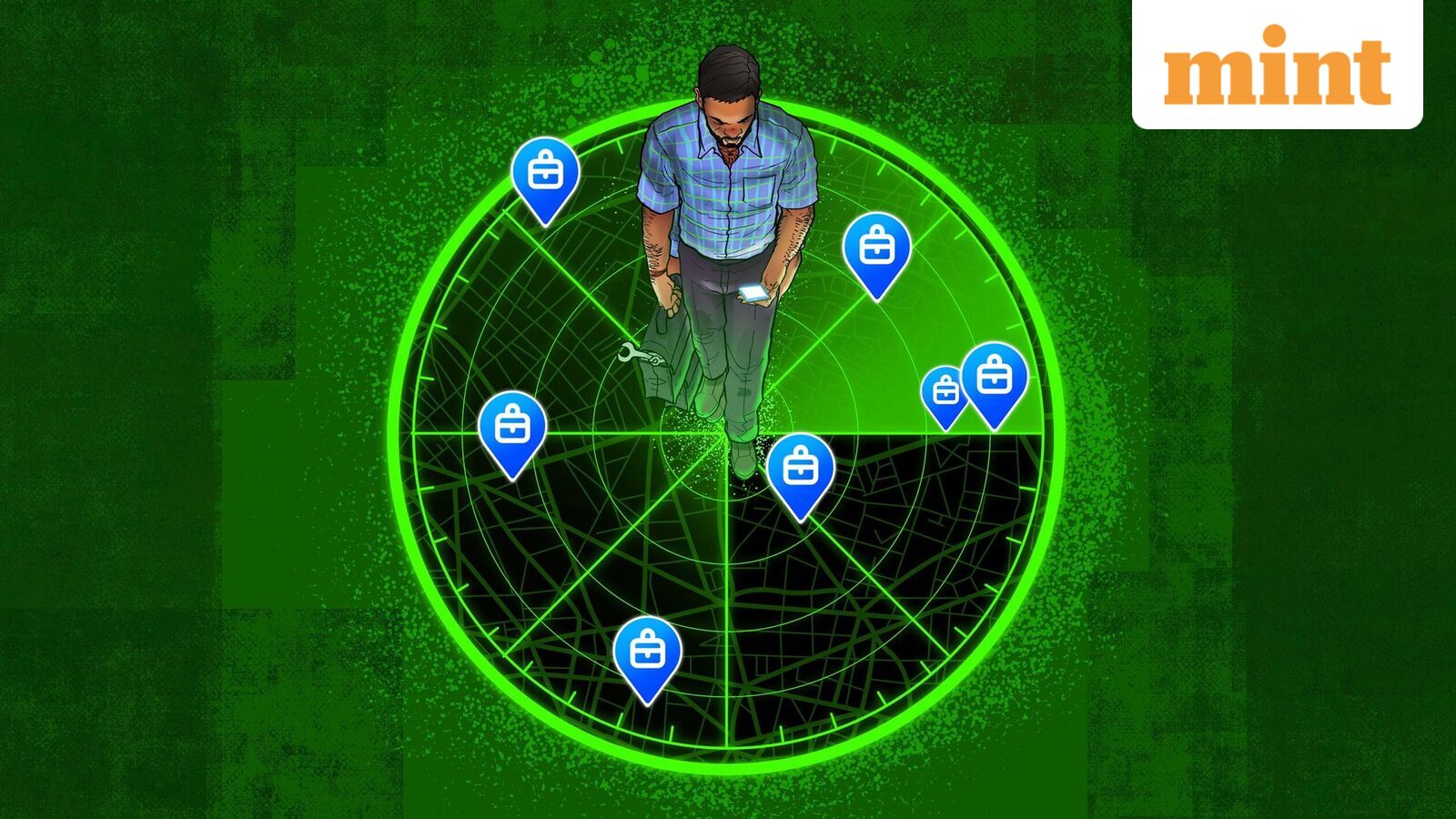

The gathering in Dharwad was not simply one other official conclave. It marked the debut of a brand new experiment in one of India’s hardest issues: connecting its tons of of tens of millions of younger individuals with work that is native.

The premise is easy to describe and arduous to execute: What if jobs, candidates, and advantages might seem on a digital map, in an app? The method eating places or petrol pumps do? A ‘blue dot’ on a display, signalling not simply the place one thing is but additionally intent: who I’m, what I’ve, what I need.

It is the lacking piece in a rustic that has already constructed population-scale digital rails for id (Aadhaar), funds (UPI), and credentials (DigiLocker). Yet, till this 12 months, stated district ability officer Ravindra P. Dyaberi, his division relied on “standard job festivals, offline banners, posters.” Students drifted into gig work or again to household farms. Employers wasted weeks chasing leads that evaporated.

The Blue Dot venture, piloted first throughout Dharwad’s ITIs and its ring of MSMEs, does one thing completely different: profiles are captured by a voice bot, verified by principals and placement officers, made seen over an open protocol, and matched to close by jobs in actual time.

Whether this mannequin can scale—or whether or not it’ll stumble like previous skilling schemes—is what drew so many voices into that scorching, crowded corridor.

Who constructed the rails

The thought of Blue Dots and the reference app got here from EkStep Foundation, cofounded by Nandan Nilekani, Rohini Nilekani and Shankar Maruwada. The basis additionally funded and revealed its protocol (known as ONEST) and credential issuance/verification as digital public items (DPGs). The DPGs are free for governments, nonprofits and personal gamers to use—every participant can put money into their very own operations and configuration to run a district pilot.

View Full Image

In Dharwad, these DPGs are utilized by the Karnataka Skill Development Authority, the division of commercial coaching & employment and the district administration. Internally, their effort is nicknamed “portray the city blue.”

Head Held High, a nonprofit, helps the fieldwork. Local teams—Deshpande Foundation, Unnati Foundation, and Gigin—are use the identical rails to match native youth to native jobs.

Nandan Nilekani, the chairman of IT providers main Infosys, and the founding chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India, is additionally EkStep’s chair. He is cited as an “inspiration and information”, however not the originator of the concept.

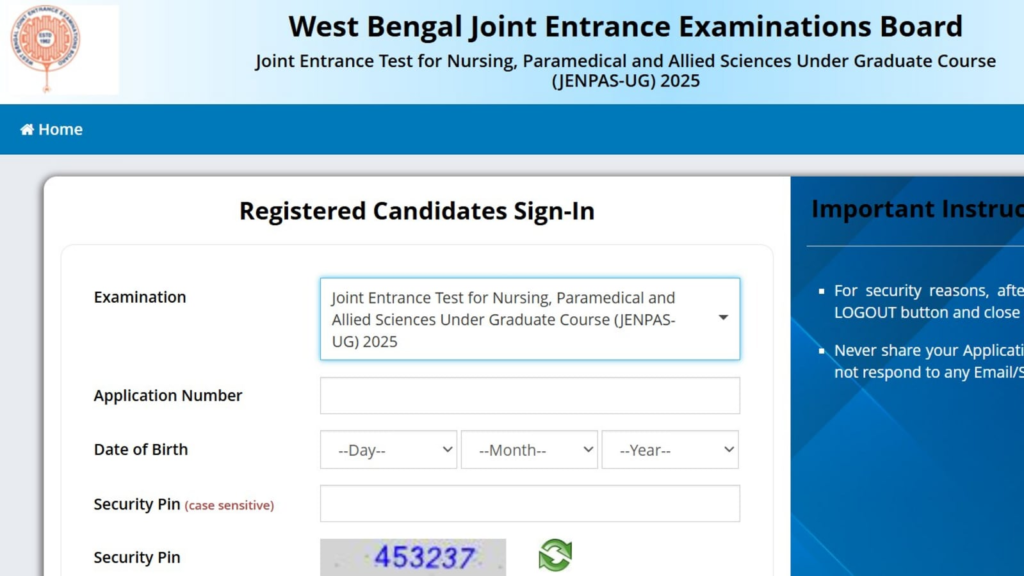

How the pilot took form

The first seeds of the venture had been planted in March 2025, when two representatives from the EkStep Foundation walked into the federal government ITI in Dharwad with what seemed like an inconceivable proposal: construct a digital map of jobs and job-seekers.

Ravindra P. Dyaberi, the district ability improvement officer of Dharwad and principal of the ITI, remembers his skepticism. “How can this be a digital platform?” he requested.

After hours of debate, he conceded.

That week, an trade affiliation set a Saturday 4 p.m. meet in Hubballi so MSMEs might see the system collectively. “Two or three agreed, then extra adopted,” stated Suresh Kumar S. Jalwad, the position officer at ITI Dharwad.

View Full Image

The group dropped the Android Package Kit (APK)—the format utilized by the Android working system to set up cellular functions—and shifted MSMEs to an internet portal/telephone onboarding, addressing machine and information fears.

The first pilot was modest. Five SMEs and a couple of hundred college students had been ‘blue-dotted’ at ITI Dharwad. Profiles had been captured by an AI-powered bot within the app that requested in Kannada or Hindi: ‘What is your trade?’ ‘Where are you willing to work?’ ‘What salary do you expect?’

Within weeks, the primary placement drive was held. Ten to 15 firms turned up, 50 college students participated, and almost 200 interviews had been performed, all tracked by DigiPass, a fast verification token.

On the bottom, the work was painstaking. Volunteers from different non-profits, like Atiya Yasmeen of Head Held High Foundation, got here in from Raichur and Kalaburagi (previously Gulbarga) to fan out throughout Dharwad. They went door to door, persuading small companies to attempt the app. Yasmeen, who had as soon as gone door to door herself, in Raichur, on the lookout for work after her father’s demise, knew the stakes. “In Raichur, we’ve got jobs. But native college students don’t even know the place to discover them,” she stated.

Some MSMEs had been sceptical. “Go away, you’ll put penalties on us later, asking what number of labourers we’ve got, whether or not we’re paying tax”, one firm instructed Yasmeen.

View Full Image

Convincing them required backup. Placement officers accompanied her, vouching for the venture’s legitimacy. Industry associations had been introduced in to ease the distrust.

Meanwhile, the AI bot itself was studying in actual time. Students remembered the glitches. “It stored saying, ‘Sorry ma’am, sorry ma’am,’ when one woman instructed her identify,” a trainee laughed. Teachers had to prod from behind: Speak loudly, don’t be afraid, it’s solely a bot. Calls generally dropped midway.

To cope, the group instituted nightly area escalation calls. “We listed what went proper, what went unsuitable—the bot mishearing names, questions complicated college students, industries asking us to change the APK,” Yasmeen said. “Next day those fixes would go in.”

The method was not restricted to Dharwad. In Vellore, Tamil Nadu, a role-bot was deployed on the Darling Residency lodge to display candidates for housekeeping and front-desk roles. The bot requested questions in Tamil, recorded solutions, and despatched summaries to the HR desk. “It was the primary time we might pre-screen within the native language with out employees sitting by 50 interviews,” the supervisor stated.

By the summer season, 350 MSMEs and over 1,100 college students had been blue-dotted throughout Dharwad district. Job-seekers had been receiving interview calls even earlier than finishing their coaching. Some MSMEs made their first ever digital hires.

At ITI Dharwad, Dyaberi and his group organized the primary placement drive utilizing the brand new system. 10 to 15 industries and 50 college students participated. Nearly 200 interviews had been performed in a single day by DigiPass. For the primary time, employers might see verified abilities on their screens earlier than assembly a candidate.

View Full Image

For Suresh Kumar, a placement officer at Government ITI Dharwad, the change was jarring.

“Before the Blue Dot, it took me a minimum of every week or 15 days to set up a placement,” he recalled. “We had to visit the industries, collect their requirements, call back our trainees—even those who had passed out years earlier—and then arrange a campus interview or a mela. If it was a bigger event, I had to prepare the whole ITI. It felt like a wedding—with none of the guarantees.”

Now, the bot did the primary spherical of questions, and inside hours, the shortlist appeared.

“Five of our trainees got letters even earlier than finishing coaching,” he added.

Jobs had been as soon as introduced on scraps of paper pinned to timber—“Female wished, accountant, ₹20,000 per thirty days”. Or in tiny newspaper advertisements, or as notices pasted on workshop gates. Word of mouth carried some, rumours the remaining. For the primary time, the interviews had been being logged, verified, and matched in actual time by the system.

The multiplier impact

If the concept of a blue dot felt summary in coverage rooms, its weight was sharpest within the voices of those that lived the hole.

In Dharwad, college students like Bushra Kotwal and Farhad Anjum from native ITIs now not wait months to hear of openings. “Earlier, it might take three or 4 months,” one stated. Their stitching and embroidery profiles had been created in minutes, verified by their principal, and made seen on a map that confirmed jobs inside attain of their properties in Murgamata, close to the railway station.

View Full Image

“I need a job in Hubballi-Dharwad solely,” stated one of Shivprakash’s trainees, even after being shortlisted by Toyota and Bharat Electronics.

Others described why proximity mattered.

“Time is saved. I can spend extra with my household, and my dad and mom don’t fear if I’m close by,” said Anjum, a trainee at Vikas ITI in Hubballi. She explained how her uncles working in cities carried the strain of long commutes and separations. “That’s why local jobs matter,” she added.

For MSMEs, the frustration was simply as visceral.

“If a employee comes from distant, he’ll attempt for 2 or three months, then go away. If I rent somebody from close by, even when I pay ₹ 5,000 much less, he’ll keep,” an industrialist stated.

MSMEs sometimes spend about ₹1,000 per rent and wait weeks to fill roles. On the Blue Dot rails, time and value fall to roughly one-tenth, they stated. Every week saved means fewer delays, much less subcontracting, and extra output.

For job seekers, a digital résumé (over 80% lacked one) and a map of close by jobs means entry and selection. Keeping work native additionally circulates cash within the area—on transport, housing, meals and providers—making a multiplier impact within the district economic system.

View Full Image

Why now, why right here

The selection of Dharwad because the launchpad was not unintended. The twin cities of Hubballi-Dharwad have lengthy known as themselves Karnataka’s “second capital”—home to universities, engineering faculties, ITIs, and a stressed youth inhabitants. But industrial progress has by no means stored tempo with its mental status.

Dharwad’s paradox: The district has over 3,100 MSMEs, producing 8,000–10,000 brisker openings a 12 months. About 2,000 college students cross out if ITIs yearly. And but, MSMEs report shortages, whereas placement charges for youth stay south of 25–30%. The hole isn’t provide or demand. It’s visibility and belief.

“Even although we’re known as Karnataka’s second capital, this area by no means acquired the guardian industries,” stated Ramesh Patil, who runs Patil Electric Works, a 120-employee agency that provides elements to Bosch and Tata Motors.

Instead, Dharwad’s factories had been left to survive as feeder items. “We are surrounded by tons of of MSMEs that provide elements,” Patil added, “but the anchor industries that could have changed this region’s trajectory never came.”

Girish Nalwadi, president of the North Karnataka Small Scale Industry Association, identified that the state’s heavyweights—BEL, BHEL, BEML—had their massive items elsewhere. “BEL has acquired 12 manufacturing items throughout the nation,” he said. “There is nothing in north Karnataka.”

That absence of anchors produced one other paradox. North Karnataka exported labour to the south, whilst its personal factories remained starved of staff.

View Full Image

Looking forward

Each night, the sphere group nonetheless gathers for a 10-minute name. The notes are repetitive however important: a bot misheard a reputation in Kannada, a immediate confused a pupil, a name dropped mid-answer. The fixes are pushed the following day—a loop of trial and correction that retains the system alive.

The identical rails now carry different worth. In Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan, a scholarship that when took six months and 50 steps cleared in two minutes when DigiPass credentials had been used. Profiles that had by no means appeared in any ledger had been instantly findable.

The analogy is acquainted in India: simply as UPI made funds move as a result of everybody shared the identical rails, work begins to transfer when jobs and profiles trip the identical pipes.

The district mannequin is being prolonged by KSDA throughout the Belgaum division, with different Karnataka districts to comply with. Mysuru will check digital job festivals. Uttar Pradesh is beginning an analogous district pilot.

View Full Image

“We wished expertise to deliver collectively job seekers and job suppliers. After reviewing the pilot with college students, trade, and district officers, we’d like to scale it,” stated V. Ramana Reddy, chair of KSDA.

On the advantages facet, after Jhunjhunu, the identical method was run in Patna and Haridwar with the Piramal Foundation, the division of empowerment of individuals with disabilities (DEPwD), and the Artificial Limbs Manufacturing Corporation of India. It is now being piloted at a bigger scale in Ranchi. Separately, edtech firm Physics Wallah is increasing a pilot to convert extra college students from economically weaker sections into ‘blue dots’ and floor wants to funders.

The final phrase does stay with the human stakes. At Government ITI Mummigatti, volunteer Atiya Yasmeen recalled one boy’s quiet aid when he realized he might work shut by and nonetheless look after his widowed mom. “That was his happiness,” she stated. For him, the blue dot was not only a sign on a display, however one much less bus fare, one much less hearsay to chase, one extra hour at home. For policymakers, it could be infrastructure. For Dharwad’s college students, it is recognition. Seen by employers throughout the highway, seen by a system that had lengthy missed them, seen—lastly—within the demographic dividend India has spoken of for many years.